What Ever Happened To….

the Gavilan Mobile Computer

by John C. Dvorak

How soon they forget. Over the last few years laptops have become lightweight, powerful and almost as good as any desktop. Jump back a year to 1982 and a laptop that we take for granted today would have been a miracle back then.

In 1982 he LCD’s weren’t good. There was no backlighting. The standard of excellence for portable computing was the 20 pound Osborne I. The Compaq would emerge from the scene with its IBM version of the 20 pound Osborne. About this time an upstart company came onto the scene with a deluge of hoopla and fanfare. It was the Gavilan — the prototype for today’s modern laptop.

Gavilan Computer Corporation was founded by Manny Fernandez in February, 1982. It was believed at the time that he raised $31 million in venture capital for the start-up. Fernandez, who had been a president of Zilog, recruited John Banning, his former director of software and architecture at Zilog, to head the software development team that included two former Apple programmers and three alumni of Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC).

Gavilan’s original name was Cosmos Computer Corporation. That name was chosen because the founders believed it suggested “OS” for operating system and “CMOS” for complementary metal-oxide semiconductor. Other than the 8088 CPU and the disk-drive controller, the Gavilan used all high speed, low power CMOS components. The software would be based on an object-oriented operating system the company was developing.

Their plans seemed to combine all of the most advanced technological trends of the period into one blockbuster product. It took advantage of the object-oriented programming methods that were being developed for SmallTalk at Xerox PARC, the type of icon-based user-interface Apple was developing for the Lisa and, later, the Macintosh, the trend towards portable computing that the Osborne 1 had started, and the new CMOS technology.

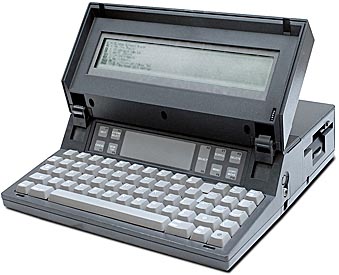

The Gavilan was a sleek looking unit in a black case of a half-clamshell design. In this respect, it foreshadowed the design of today’s laptop computers at a time when the laptop of the day was the Tandy Model 100.

Not content to merely copy existing technology, Gavilan also set out to create a touch panel, which was officially referred to as a “solid state mouse.” The touch panel, located between the keyboard and the flip-up LCD (liquid crystal display) screen, controlled the user-interface. The central area of the touch panel controlled the pointer in much the same way a mouse does. The pointer moved across the screen relative to the movement of your finger on the touch panel. There were also several separate areas of the touch panel that invoked specific functions. Tapping one of these areas with your finger would call up a context-sensitive Help screen or a Menu of basic functions. Other areas of the touch panel included commands to Select, Cancel, Extend, and Scroll. Anyone, like myself, who actually played with this pad found it to be awkward and uncomfortable. It was at the top of the keyboard and the user had to worry about hitting keys and there was no place to rest your palm.

This was the tip of the iceberg of problems for the machine. For example, although the machine used Intel’s 8088 microprocessor, MS-DOS was not included in the original plans for the computer. It wasn’t until it became apparent just how popular the IBM PC was that MS-DOS was included, and then only as an option.

Another problem was the floppy disk drive. Gavilan originally intended to use the odd 320K 3-inch format floppy drive then being promoted by Amdek and others. The prototype that was shown at the 1983 COMDEX/Spring, in Atlanta, Ga., used the 3-inch floppy drive. By the time the Gavilan began shipping, though, they had switched to the 360K, 3-1/2-inch format. Even that was problematic at a time when all the available software was on 5-1/4″ floppy disks. No matter, Gavilan arrogantly assumed that users were better off buying their software on the memory “capsules” that the Gavilan used, since the programs had to be loaded from disk into the memory capsules anyway. All the while the designers never worked on ways to transfer data to and from a desktop machine.

Finally, quantity shipments of the Gavilan didn’t begin until June, 1984 although the company kept promising 1983 dates.

In the interim, the press was told that some bugs had been discovered. This was not surprising in a product that used so many new technologies. Some veteran analysts had wondered whether the Gavilan would ship at all. Fixing the bugs, however, required some fundamental changes. Those changes caused the more than six month delay in quantity shipments between late 1983 and June, 1984.

When the Gavilan finally did ship, there were not enough customers. At a list price of $3,995 for the 96K regular model with a 16 line by 80 character LCD screen and $2,995 for the 64K SC model with an 8 line by 80 character display, it was too expensive for a machine that didn’t have the IBM PC’s “full” 256K of RAM.

There were also other machines on the market by this time that had the features users really needed at a lower price. Data General’s DG/One, Hewlett-Packard’s HP110, MicroOffice’s RoadRunner, Morrow’s Pivot, Quadram’s Datavue 25, and Zenith Data Systems’ ZP 150 were all available at about the time the Gavilan was actually shipping. All had comparable memory and features, and many at lower prices.

Another major problem was the method of distribution. Gavilan tried to use VARs (value-added reseller) to sell their product. On the whole, VARs were not as well established in portable computers and there were fewer of them to sell the Gavilan. This made it even more difficult for the company to recoup its large development costs and within six months of releasing the Gavilan Mobile Computer the company had collapsed into bankruptcy.

The computer itself proved somewhat more durable than the company itself. The following year a group calling itself the Gavilan Users Group (GUG) was building Gavilans from a stockpile of parts and accessories acquired at a public auction and selling the once costly machine for $800. By 1986, GUG had 12 branches in the U.S.

Manny Fernandez licked his wounds and after the failure of Gavilan in November, 1984, he became CEO of Dataquest, Inc., the market research firm. He left there in January, 1991, to take a similar position with Dataquest rival the Gartner Group.

A lot of factors kept radical portable computers from catching on in the early and mid-eighties. The most interesting was the dubious assumption that because of the popularity of the Osborne 1 there must obviously be a crying need for portable computers. Actually, most customers bought the Osborne to use as a cheap desktop computer. What made it successful, and lead to the company’s demise, was its low price combined with the bundled software it offered. Gavilan failed because it missed the point.