Whatever Happened to the Seven Dwarfs?

Dwarf One: Burroughs

by John C. Dvorak

IBM and the Seven Dwarfs — It was a coinage of the mid-1960’s as IBM dominated the computer business. IBM and the Seven Dwarfs was how the business was described. By 1965 IBM had a 65.3-percent market share of the industry. The seven dwarfs shared the rest. They were: Burroughs, Sperry Rand (formerly Remington Rand), Control Data, Honeywell, General Electric, RCA and NCR. The following is the story of Dwarf One: Burroughs

The founder was William Seward Burroughs. Born around 1855 he began his career as a bank clerk in the 1870’s. His claim to fame was the invention of an adding machine which he began to develop in 1880 and had patented in 1888. In 1886, just before the patent was issued, he started the American Arithmometer Company in St. Louis.

Burroughs died in 1898 and in 1904 the company, thriving, was moved to Detroit. A year later it was renamed The Burroughs Adding Machine Company in honor of the founder.

The company soon became the dominant manufacturer of adding machines and was branching out to other office equipment including check protection machines and typewriters. They were flying high. When the computer was unveiled after World War II the company took a look at it and realized that it would have to get into that business. It was the future of, uh, adding machines! IN 1953 it made its intentions clear by dropping “adding machine” from its name and it became the Burroughs Corporation.

The company, which had close military links due to war efforts toyed with scientific computers in 1953 and introduced a machine called the UDEC — the universal digital electronic computer. This was followed by the UDEC II. Little is known of these machines today and references are few, but it seems to have been an early scientific or ballistics computer. Neither were commercial products.

In the mid 1950’s there was an interesting dichotomy regarding computers. There were two distinct camps of designers. One built machines using a binary architecture and the other built machine using a decimal architecture. The binary machines were seen as best fit for scientific computing. The decimal machines were seen as best fit for business computing. Because Burroughs was deeply entrenched in the banking business it needed to sell a decimal computer to compete. This is the heyday of tube based computing. Today we seem to think that the only tube computer was the ENIAC. In fact all the of the computers that came out during the early and mid 1950’s were tube machines. Burroughs, to get up to speed, quickly bough one of the leaders in tube computing: ElectroData and it’s line of Datatron machines. It wanted the upcoming Datatron 205 machine to be a Burroughs 205. This was in 1956. I’m not sure but it’s possible that ElectroData was the first computer company that used an uppercase letter within its name.

The 205 had a number of interesting characteristics besides being a decimal computer. It utilized an spinning magnetic drum with average access time of 8.5 milliseconds. The drum had two sections. The high speed access section which had each piece of data duplicated 10 times and offset on various bands on the drum to increase the access time by 10. Here the average data access time was .85 milliseconds. Nothing to sneeze at by any standard. These quick accesses and speed to the processor seemed to be the most important thing about mainframe computing. I/O. The access time was often faster than the calculation times. The machines cpu power was measured in kips (thousands of instructions per second). An instruction would take two milliseconds.

This speedy I/O was part of the reason that mainframers scoffed at the microcomputers of the 1970’s when they hit the scene. While the early microprocessors maybe did 80,000 instructions per second — far faster than early mainframes, the micro’s I/0 was appallingly slow. Even to this day the processor is spending most of its time sitting idle — waiting for something to do.

Burroughs made a number of other machines. mostly upgrades to the 205 over the next few years.

Then came the big splash in 1962 — the introduction of the B-5000. This machine is revered by computer aficionados. It was the most revolutionary machines of its day. I discussed this machine with Burroughs expert, Professor Alan Bateson, University of Virginia. He’s convinced that this was one of the most important breakthrough machines ever developed. He said, “If people could read the specifications of this machine with 1960’s eyes, they’d be astonished!” All the computers that would come from other companies after the introduction of the B5000 would use it’s design ideas.

The chief architect of the machine was the fabled Bob Barton. It was the first commercial machine to employ virtual memory, arithmetic stack control and other modern features. It also destroyed the notion that a business machine had to be decimal and this machine was sold as both a scientific machine and a business machine. It combined binary and decimal functionality and its machine language was ALGOL. It ran at an astonishing one megahertz.

This machine was so famous that one of the most popular buttons of the era said, “I touched the B5000.” The B5000 used discrete logic (transistors) although later versions adopted IC’s. The machine never caught on in scientific circles and ended up mostly in banking where it dominated. But this market was a disappointment considering the importance and potential of the machine. What was happening was that IBM’s superior sales force was killing companies like Burroughs. The notion that people will always buy the best product (Bill Gates like to spew this dictum to excess) was proven to be nonsense. The B5000 line was to be Burroughs swan song in many ways.

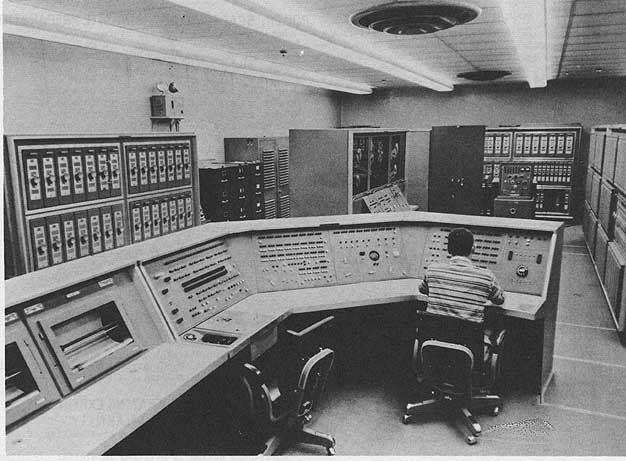

The company did develop other concepts never before seen, to little avail. It had a division in Pennsylvania that worked almost exclusively for the government with high-end computers including secretive machines developed for the NSA including the D825 — the worlds first multiprocessor computer. All the SAGE anti-missile system machines were developed by Burroughs.

It was an uphill battle against IBM and the company began a relationship with Sperry largely due to the fact that it worked with an early RAND spin-off called SDC (Systems Development Corporation) which worked with Burroughs on SAGE. Burroughs bought SDC in 1980 and merged with Sperry shortly thereafter in 1986 thus forming Unisys.

In fact the merger was actually a $4.8 billion buy out of Sperry by Burroughs. Over time the new company evolved into a computer services company and its days of breakthrough inventions and leadership epitomized by the B5000 are a thing of the past. The name Unisys came out of an employee name change contest. Apparently 10 people all picked this new name. The man who started it all, William Seward Burroughs, was simply forgotten.

Links:

Other Dwarfs: Burroughs, Sperry Rand (formerly Remington Rand), Control Data, Honeywell, General Electric, RCA, NCR